Funding HVAC, BAS, and Central Utility Upgrades with Utility Rebate Incentives

Most large HVAC and central utility projects are justified on reliability, not energy.

Chillers reach end of life. Building automation systems become obsolete. Steam systems leak. Compressed air loads increase and compressor availability loses redundancy. These projects move forward because the risk of failure becomes unacceptable.

What many owners miss is that these same projects often contain significant energy savings. That is especially true for building automation system upgrades, where the largest value frequently comes from improved control logic rather than new hardware alone. Utility rebate programs exist specifically to capture and reward those savings.

When those savings are properly identified and quantified, utility incentives can fund a substantial portion of project cost. In today’s incentive environment, it is common for 30 to 75 percent of total project cost to be funded through rebates, depending on the program and project type. In some cases, even maintenance and repair work qualifies.

This post lays out a practical framework for how that happens, when it works, and why controls and system-level thinking matter more than individual equipment efficiency. The concepts apply nationally. We are based in New Jersey and reference New Jersey programs where they provide a clear, real-world example of incentives done well. New Jersey currently offers some of the strongest incentive levels in the country, with funding authorized through mid-2027. For an introduction on how we support these efforts, see our HVAC, BAS, and utility rebate consulting page.

Reliability-Driven Projects Are the Ones That Get Funded

Across hundreds of projects, the same pattern shows up again and again. The projects that perform best financially and operationally are reliability-driven first.

1) Reliability and Performance Come First

The strongest projects start with systems that already need attention: aging chillers, end-of-life BAS platforms, failing steam infrastructure, or compressed air systems operating without redundancy.

These projects are already justified from a reliability standpoint. Energy savings are not the primary driver, but they are almost always present.

BAS upgrades deserve special mention. Aging control platforms introduce operational risk, cybersecurity concerns, and long-term support issues well before mechanical equipment physically fails. Owners are often forced to act when vendor support or software compatibility disappears. When handled correctly, energy optimization becomes an enhancement to a reliability project, not a distraction.

2) Energy Savings Are Almost Always Embedded

Reliability upgrades almost always create overlapping energy opportunities.

The biggest mistake is treating projects as one-for-one replacements. Swap a chiller. Replace a controller. Install a new compressor. Move on.

The real value shows up when the overall system is improved, not just the equipment. A chiller replacement paired with proper chilled water plant control strategies behaves very differently than the same chiller dropped into an unchanged plant. The same is true for air systems, compressed air, and steam distribution.

In practice, the size of the energy savings depends on how the system is operated once the reliability work is complete.

3) Incentives Fund the Capital

When energy savings are quantified correctly, utility incentives become real money.

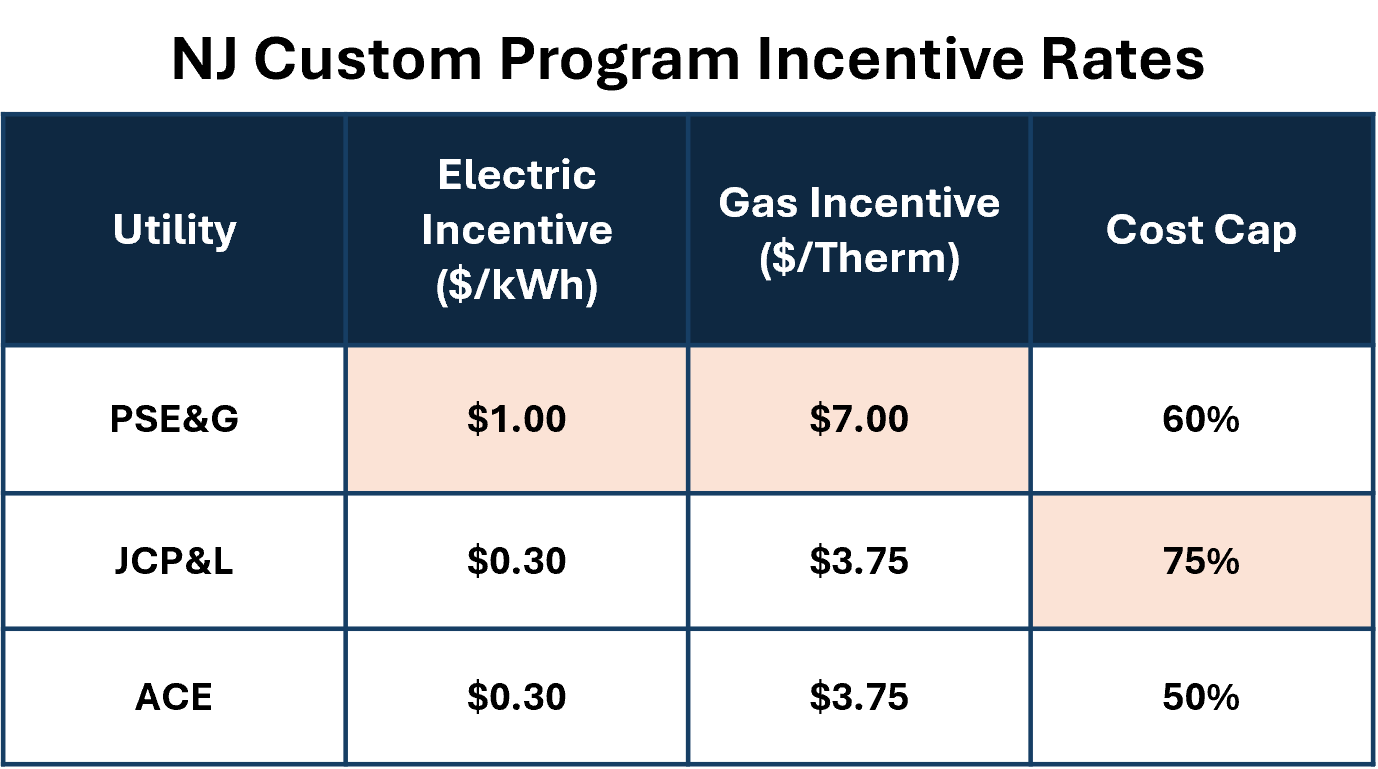

Across the U.S., most large utilities offer some form of custom rebate program intended to fund system-level efficiency improvements that fall outside prescriptive measures. New Jersey is a useful example because these programs are currently very strong.

The key point is not the specific rate. It is the mechanism. Custom rebate programs reward projects that improve how systems actually operate. One-for-one equipment replacements tend to produce modest savings and modest rebates. System-level work, BAS upgrades, sequencing changes, and plant optimization are what generate savings large enough to materially fund capital projects.

Incentives are not administrative exercises. They require rigorous, defensible engineering analysis.

Where This Approach Works Best

This approach works best where energy use is large enough, and systems are complex enough, for system-level improvements to matter.

Facilities with central plants, large air systems, or significant process loads consistently see the strongest results. Hospitals, pharmaceutical campuses, universities, and other mission-critical facilities tend to be good candidates because they combine high energy intensity with operational complexity.

Aging infrastructure is a strong indicator. When systems already have known reliability issues or deferred maintenance, incentive-funded optimization often layers in naturally alongside work that needs to happen anyway.

Smaller buildings with single rooftop units generally do not justify the effort required for large custom incentive programs. The scale of savings is often too small to support the analysis and administration required for custom rebates. For these facilities, upgrades are typically better suited to prescriptive rebate programs, which use simpler calculation methodologies and more streamlined rebate pathways. The incentive amounts are smaller, but the effort is better aligned with the level of funding available.

That distinction should not be confused with ignoring optimization. Vacancy and partial occupancy are absolutely BAS problems. In portfolios with underutilized or intermittently occupied buildings, some of the largest and fastest savings come from operational strategies implemented through the BAS. Scheduling, setbacks, airflow minimums, and occupied standby modes often matter more than capital upgrades in these scenarios. This is a core part of our BAS optimization work, and we discuss it in more detail in our article on HVAC optimization challenges in vacant and underutilized buildings.

Ultimately, scale matters. Utility incentives are driven by measurable energy savings, and those savings are most often found in central plants, large HVAC systems, and large process loads.

Two Primary Delivery Paths

In our experience, successful incentive-funded projects often fall into one of two paths.

Path 1: Capital Upgrades Through the Custom Program

This is often where the largest incentives exist, and where the most value is either captured or left on the table.

Custom programs fund system-level efficiency improvements tied to measured or modeled savings. Program names vary by utility, but the structure is similar. Incentives are capped as a percentage of installed cost and reward projects that embed controls optimization alongside capital upgrades.

This path most often applies to BAS upgrades, chilled water plants, large air systems, compressed air systems, and other central utility infrastructure.

For reference, links to the current New Jersey custom programs are provided below. New Jersey rebates, particularly within the PSE&G service territory, rank among the best in the nation.

PSE&G: https://bizenergy.pseg.com/advanced-custom-program#no-back

JCP&L: https://www.firstenergycorp.com/save_energy/save_energy_new_jersey/for-your-business.html

Atlantic City Electric: https://homeenergysavings.atlanticcityelectric.com/business/prescriptive-custom-programs

Achieving incentive levels in the 60 to 75 percent range requires careful alignment between reliability goals, control strategy, and defensible savings assumptions. That alignment does not happen automatically.

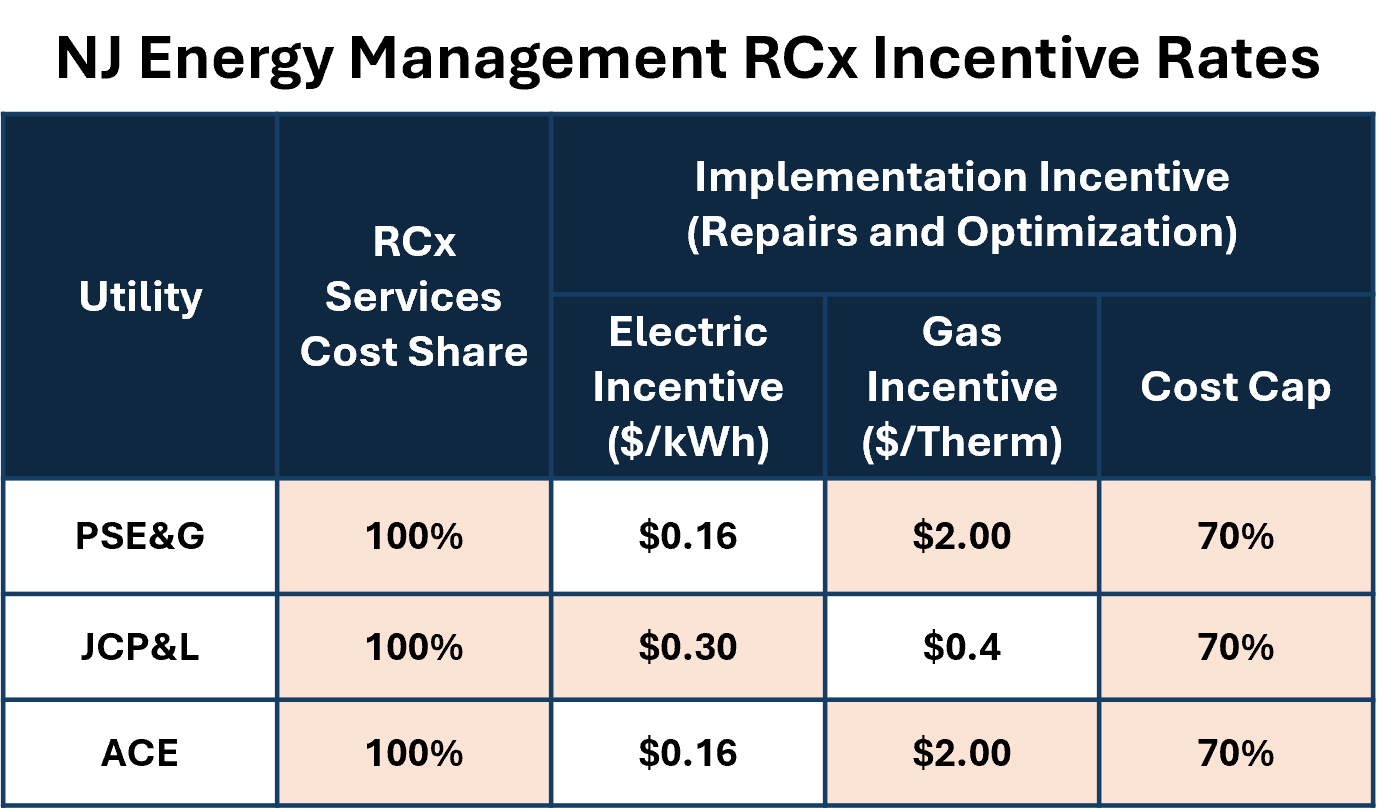

Path 2: Repairs and Optimization Through Energy Management (RCx)

This path applies when major capital upgrades are not planned, but systems are clearly not operating as intended.

Energy Management or RCx programs focus on repairs, controls corrections, and operational optimization rather than equipment replacement. Utilities typically fund the RCx engineering study and a significant portion of implemented repair costs when savings can be verified.

For reference, current New Jersey Energy Management RCx programs include:

PSE&G: https://bizenergy.pseg.com/energy-management-program#no-back

JCP&L: https://bizsolutions.energysavenj.com/retro-commissioning-rcx/

Atlantic City Electric: https://homeenergysavings.atlanticcityelectric.com/business/energy-management-program/rcx

This path is especially effective for aging facilities where replacement is not yet justified or capital budgets are constrained.

Why New Jersey Is a Useful Case Study Right Now

Utility incentive structures vary widely by state and utility, but New Jersey is currently one of the strongest rebate markets in the country.

Each electric and gas utility now runs its own programs. While that adds complexity, it has also driven incentive levels significantly higher. Construction cost caps have increased, repairs are now eligible through Energy Management programs, and funding is in place through at least 2027.

This combination makes New Jersey a useful real-world example of how incentives can materially change project economics. The window is real, but not permanent.

Why Controls Matter as Much as Equipment

Across both incentive paths, the same theme dominates.

Controls matter just as much as the equipment itself. In many projects, they matter more.

Replacing equipment with a higher-efficiency model will almost always reduce energy use. But equipment-only upgrades rarely unlock the full savings potential of a project. That happens when the entire system is optimized, not just the component being replaced.

Chiller projects are a good example. Installing a new, higher-efficiency chiller will save energy on its own. Pair that same project with a chilled water plant optimization effort and the impact is much larger. Optimizing condenser water temperature, staging logic, and plant coordination improves the performance of the new chiller and every existing chiller that remains in service. The result is lower overall plant energy use, not just incremental gains from one piece of equipment.

This dynamic applies across HVAC and utility systems. Air systems, compressed air systems, and steam systems all benefit when control strategies are addressed at the system level. Reset strategies. Staging logic. Minimums. Scheduling. Standby modes. These are often the levers that determine real-world performance.

ASHRAE Guideline 36 provides a practical reference for what good control looks like in operating buildings, as discussed in more detail in our article on why ASHRAE Guideline 36 is important for real-world HVAC performance. While it is often associated with airside control, it also includes best practice chilled water plant optimization strategies that support system level performance.

Why Incentive Value Is Often Left on the Table

Custom incentive programs are consistently underutilized, even on projects that are otherwise well suited for them.

In practice, incentive dollars are most often lost for a few predictable reasons:

Incentive work is nobody’s primary responsibility

Energy savings are treated as a secondary outcome rather than a core project deliverable

Design teams underestimate the savings potential from controls and system-level optimization

Best-practice control strategies are only partially implemented

Owners lack the internal bandwidth to manage incentive development and follow-through

Contractors are focused on delivery and schedule, not defending energy savings assumptions

There is no alignment between the effort required to pursue incentives and the value of the rebate

What consistently works better is a different role definition.

Successful projects assign a dedicated, incentive-focused energy consultant whose responsibility is to ensure that the project actually delivers energy savings. This role is distinct from the design engineer and from the commissioning agent. The focus is not just functional performance, but quantifiable energy outcomes.

The most effective way to align that responsibility is through a success-based or performance-aligned fee structure, where the consultant’s compensation is tied directly to achieved energy savings and recovered incentives. That alignment changes behavior. It ensures that optimization strategies are fully embedded, that savings assumptions are defensible, and that the energy scope is carried through construction, commissioning, and measurement and verification.

When incentives are supported by a dedicated energy savings advocate, they stop being a paperwork exercise and become an integral part of how reliability-driven projects are scoped, optimized, and executed. We outline how this role fits into real projects and how we support incentive strategy, analysis, and follow-through on our HVAC, BAS, and utility rebate consulting page.

Applying This Approach Beyond New Jersey

Most facilities already have the projects. The difference is recognizing which ones can be turned into funded opportunities.

The practical next steps are simple:

Screen planned or in-design projects for incentive eligibility

Determine whether the Custom or Energy Management path fits best

Ensure controls optimization is fully embedded and carried through commissioning and M&V

Reliability-driven projects and energy incentives are not competing priorities. When approached correctly, they reinforce each other.